AI 101 for Post-Docs

This is the written version of a brief introductory presentation for post-docs in technical fields other than computer science on how current AI systems work, how to use them, and what I view as effective ways of using AI on a day-to-day basis - an approach I like to think of as “Getting More Done by Being Lazy with AI.”

There’s a famous Star Trek scene where, when transported into the past, Scotty talks into the mouse of an “ancient” (1980s) computer in a vain attempt to get it to work. Eventually, he discovers the “keyboard” is necessary to input his request to the computer. While keyboards are still here, we’re now beginning to move out of this primitive era with the assistance of artificial intelligence (AI) - specifically large language models (LLMs). Essentially, LLMs provide a novel way to interact with computers, letting us use natural language to access and manipulate information - providing an interface which Scotty would be more comfortable with.

A simple approach is to conceptualize an LLM as an informed (though not infallible) conversational partner - somebody who’s got great general knowledge whom you could trust with a task that might take you a few minutes to a few hours. What sort of tasks? Almost anything: writing, research, coding, making images, or more. But whatever the task, you have to be able to describe it in words!

“Prompt engineering” is the fancy term for describing your problem in a way which is likely to give you the response you’re looking for. This can start by having the right frame of mind - imagining that you’re describing the problem to somebody you ran into in the hallway from scratch, rather than somebody who already has an idea of what you’re talking about.

Specific points to watch out for are things like defining what criteria your answer needs to meet: is it a programming problem in a certain language, or using a specific API? Does your answer have to meet a word count? Should it be in a different spoken language?

Another point is specifying the information you want to consider: should it be from academic sources? Should it be looking for the answer inside a specific article or piece of text? Are you including this text in your query? If you’re including a link, can the engine you’re using access it and look through that information?

Finally, define the scope of the problem: whether you’d like a high-level summary or detailed, point-by-point explanation, a cartoon or a realistic drawing.

Next, we’ll look at how this prompt is taken and magically transformed into an answer.

The Illusion of Memory

LLMs are trained to predict the next item in a sequence given a history of previous values. These values are called “tokens,” which represent letters or characters. Essentially, given a sentence or paragraph, it predicts the next word. Add this word onto the previous sequence, repeat, and you get a computer program that can write.

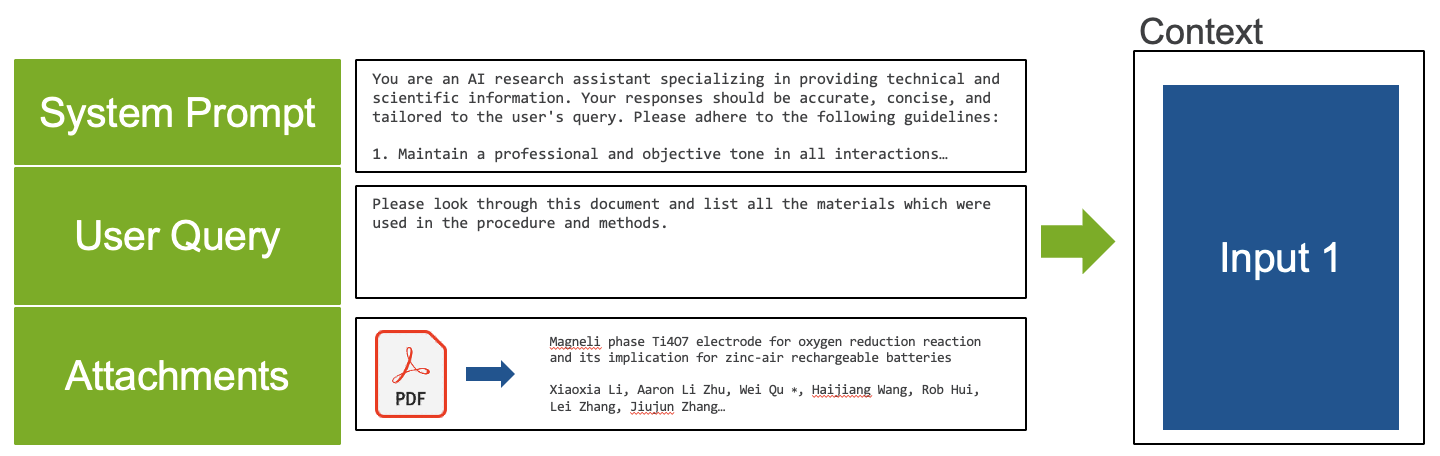

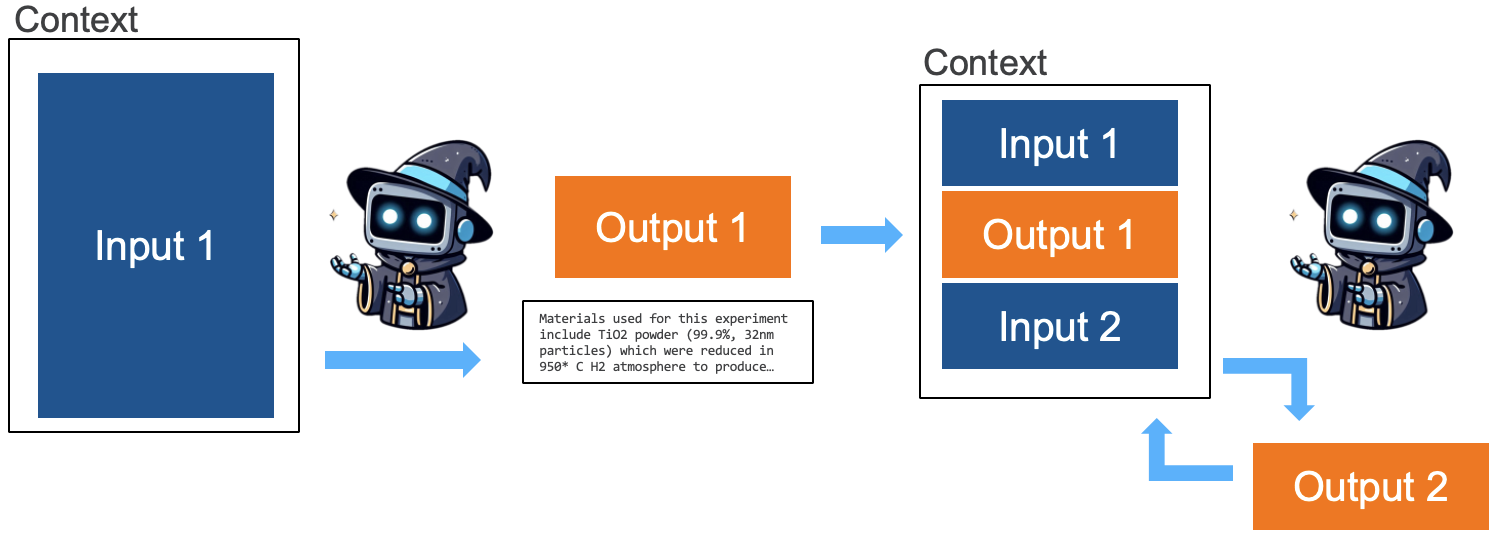

This input to the model is called the “context.” Part of the context is provided to the LLM by the user’s request, but it’s also supplemented by the interface system around the LLM which adds a “system prompt” to improve performance and guide the LLM’s behavior. Additionally, users to some systems can add other information - like PDFs with text - which are converted and added into the context.

The LLM takes the input context and creates a response - predicting words until it thinks the sentence should end. This is the “output” from the context, which is appended to the previous information so the LLM appears as though it “remembers” the last part of your conversation and you can ask a follow-up question.

Currently, LLMs all have limits to the amount of information which can be stored in the context. Different systems handle this limitation differently, but it generally means that in very long conversations or including large documents, the model might not work as well as with shorter ones since it begins to “forget.”

This basic interaction loop is the process behind AI “chat” systems like ChatGPT and Mistral. Other systems focused on coding like GitHub Copilot or Codestral also use this same loop, but with LLMs that are fine-tuned on providing good answers to coding problems.

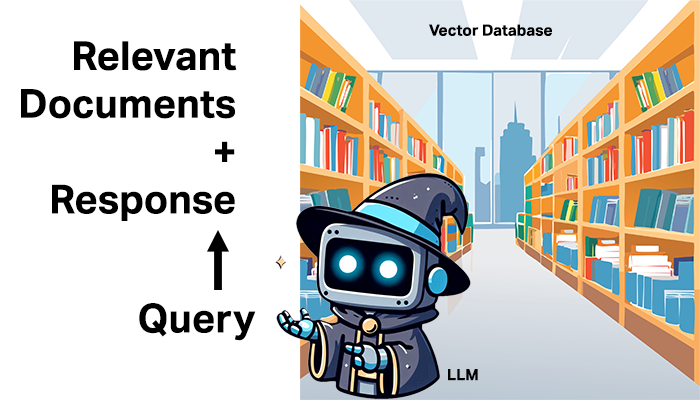

Other systems can vary this approach to provide different utility. One well-known problem of LLMs is their ability to “hallucinate” - basically, given that all they do is predict the next likely word in a sequence, they can create outputs which seem highly believable but aren’t factually true.

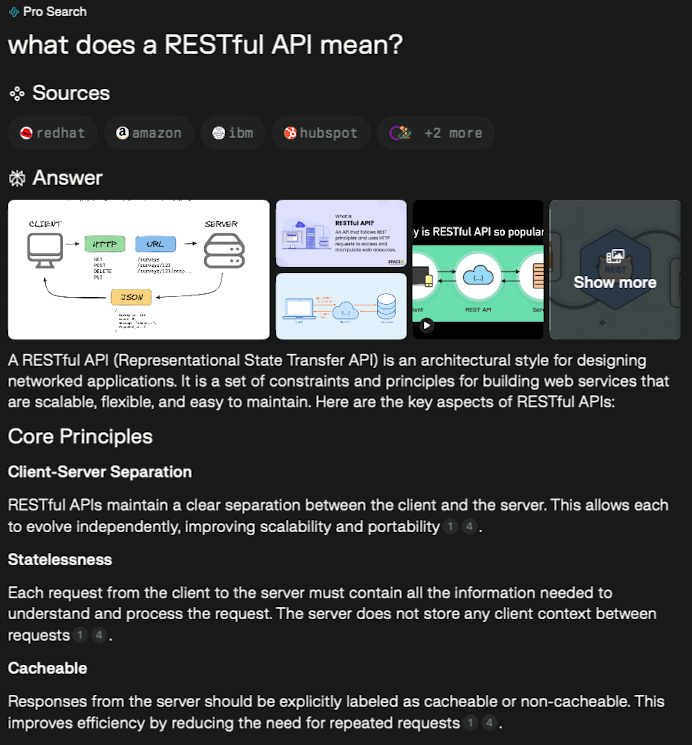

One way to augment this loop is called “retrieval augmented generation” (RAG), which links the output to specific pieces of information which can be checked and verified by the user. Essentially, this is done by crunching down the context into a fixed-size “embedding” that’s compared to a database of information to find the best matching documents. Perplexity is one tool which uses RAG to provide links related to a query.

Embeddings can also be used in different ways - for instance, when a user wants an image, the embedding can be applied as the input to a diffusion model designed for image generation from text. Tools like Microsoft Designer, Midjourney, and Adobe Firefly work this way.

Using AI: 90% Boring, 10% New

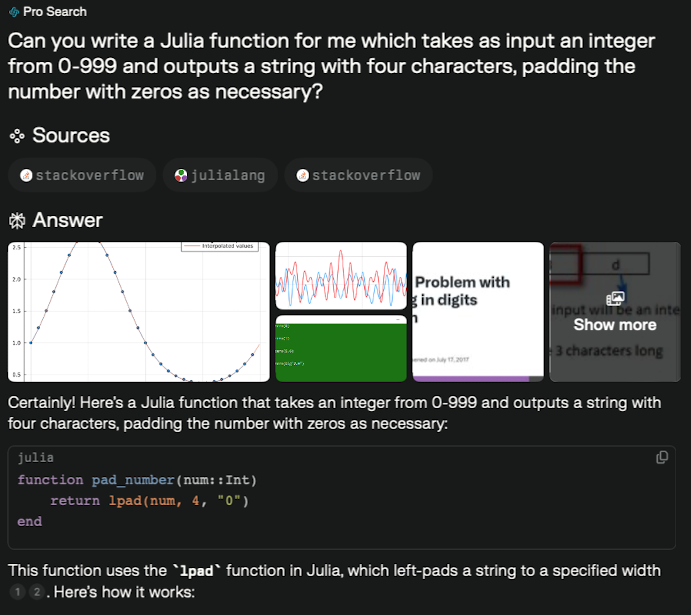

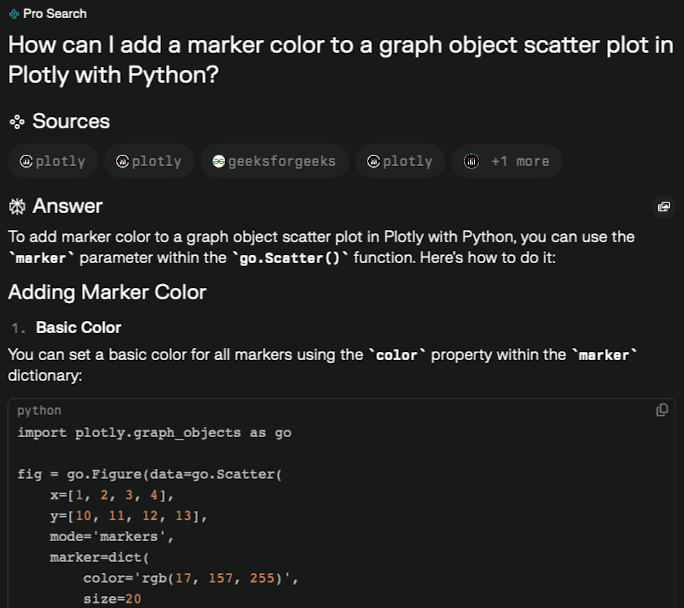

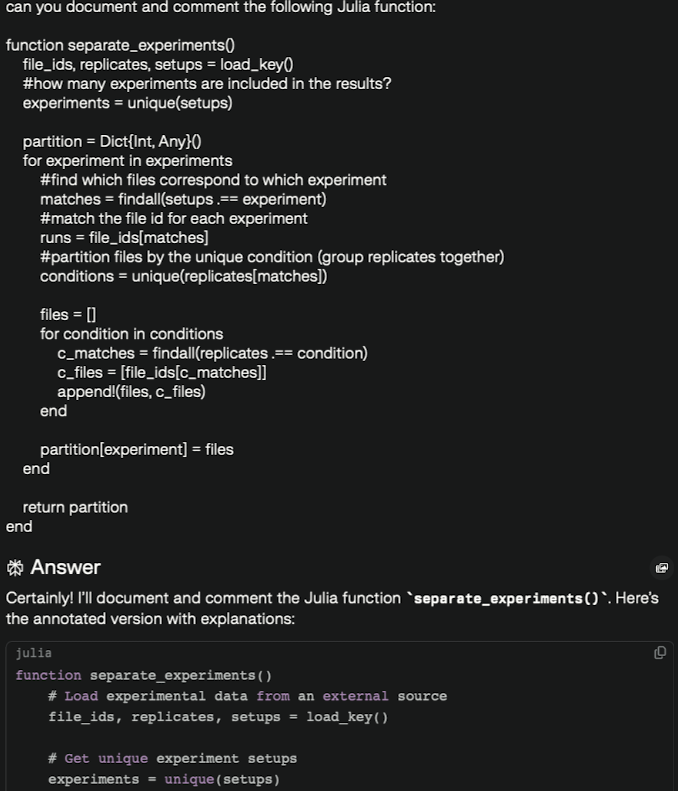

Given all that, a natural response is “that’s cool - how does this actually fit into the work I need to get done on a day-to-day basis?” What I’ve found is that for the majority of my uses of AI, I’m not asking for anything wild - I’m asking the AI to do a task I could carry out perfectly well myself, it can just do it faster and get it right most of the time. This is what I call the “get more done by being lazy” principle applied to AI.

Let’s look at some examples by digging through the history of my queries in Perplixity and other tools. I’ll break these down into a few “categories” I find myself using a lot:

Annoying but easy coding

I’ve been coding since I went to summer camp in 5th grade and started to learn C++. I will freely admit that despite over 20 years of experience, there are many tasks I still forget how to do, don’t want to do, or just find downright annoying. Let’s look at a few AI can rid me of:

String formatting

Remembering matplotlib & Plotly API calls

Doing documentation & writing tests

Resolving writing issues

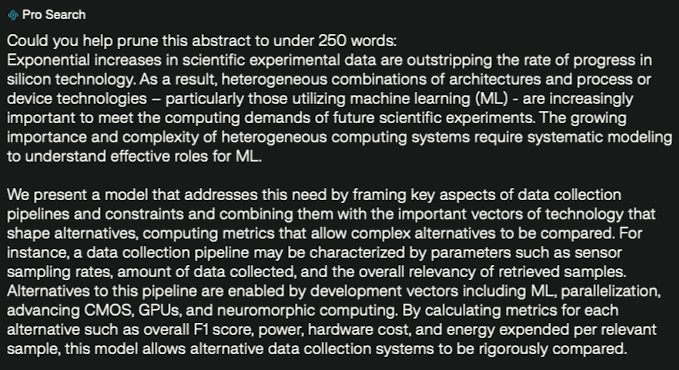

Sometimes, you’ve written the perfect abstract but suddenly find it’s over the word limit. Writing in LaTeX also becomes much more pleasant when you don’t have to write LaTeX.

My Abstract is too long, help

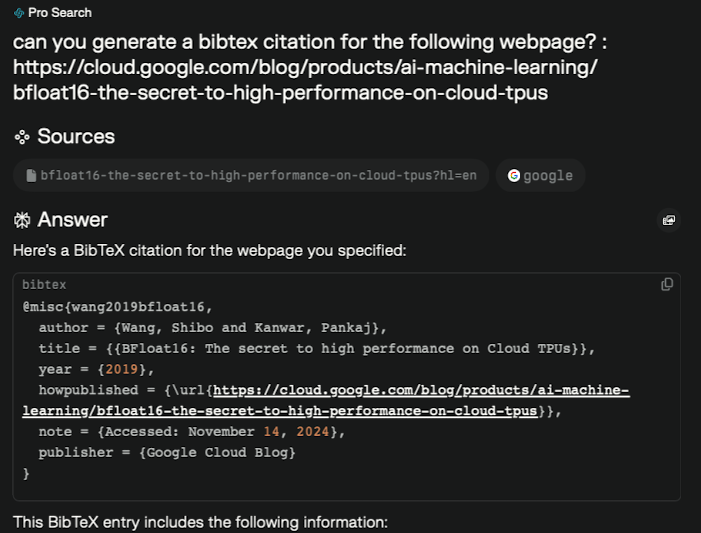

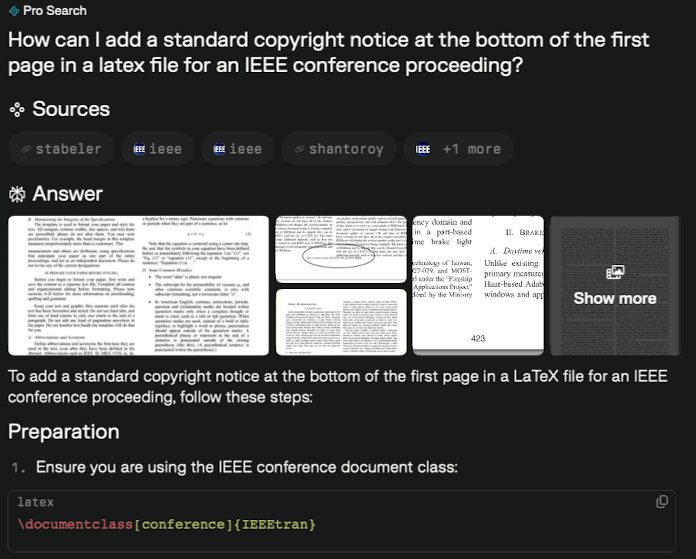

LaTex.

More LaTeX.

What’s the name of that tool & how do I use it?

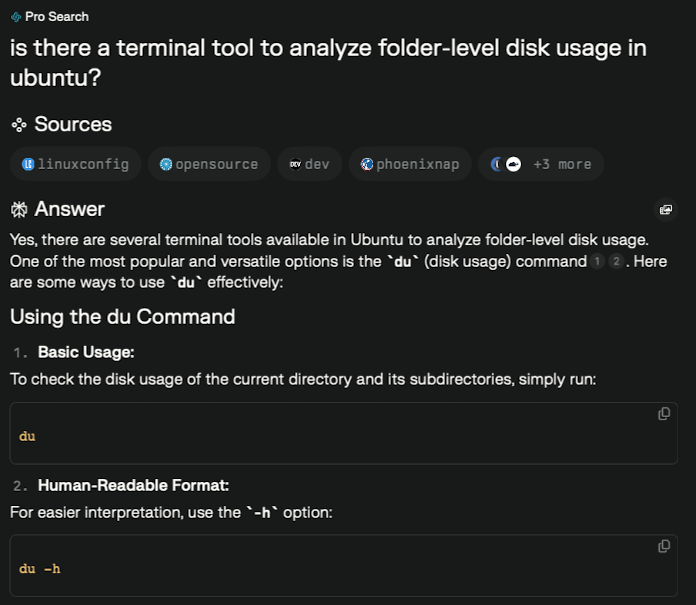

Names of *nix commands are rooted in slow teletypes and strange acronyms, use inconsistent flags, ordering, and generally contain other major and minor nightmares. Generally, AI can help provide me with the magic terminal command or other software tool I need to help solve a problem without diving into man pages or documentation.

Disk usage in Linux

Managing partitions

What version of SPICE is free?

Decipher these error hieroglypics

Error messages almost never tell you something useful, but AI can help translate by being your own personal StackOverflow.

Help me fix my git repository

Why is this kernel missing from my IDE?

What paper is this fact I remember from?

Sometimes there’s a bit of knowledge floating around in your brain you want to cite in a paper, but you cannot for the life of you remember the author or paper title. A RAG-enabled AI tool can sometimes help get you out of this quagmire.

Fixing my own embarrassing misunderstanding(s)

There’s always some pieces of knowledge we either feel like we everybody else knows about or have some specific facet which we don’t understand. Getting into a short conversation with an LLM can help remedy these situations.

Making ClipArt so people have something to look at

We’ve all faced the horror of a blank slide which needs just a single image so people have something to look at while we speak. Also, want to guess where the cartoons in this presentation came from?

10% New

Finally, there’s the stretch goals of AI - things which fall under “I’m not sure if I can do this, but I’ll try to work through it piece-by-piece.” I’ve used this approach for tasks like porting software to CUDA.

Summary

Let’s be clear: AI doesn’t always work, even within the example I’ve just given. You always have to check the answer which AI gives you. But most of the time, the answer it gives is good - and AI takes a minute or so to do a task that might have taken an hour or the entire afternoon. This has lead to huge speed-ups in some of the work that I’ve been able to do.

There’s a lot of hype around AI which it’s easy to get caught up in. But for now, I like to keep in mind the fact that once, word processors were scary and new. In seconds, you could center lines, justify paragraphs, correct typos, and print multiple copies of a document you drafted that morning. At the time, this was revolutionary! Each of these tasks was slow and painstaking on a typewriter. But now, we don’t even think of these tasks as “hard” - they’re solved, and we can spend our time on other problems. I think of current AI systems as falling into the same category: automating problems which are slightly difficult but also essentially boring. That’s where I’ve found them to be most effective and provide the greatest speed-up to my own work.